Outline of the lesson

In this lesson I am inviting you to start exploring and understanding the tense and problematic relations between reproductive work duties and knowledge production duties in academic and research institutions. The lesson is structured in 2 main sections

- Evidence of the problems at stake, concepts and terminology

- Work life balance tensions in academic and research institutions

- Good practices and inspiring examples from Research Institutions: inspiring sources for actions and an interesting case of a proactive approach on gender sensitive teleworking measures from the TEAGASC and the Gender SMART Project.

Evidence of the problems at stake, concepts and terminology

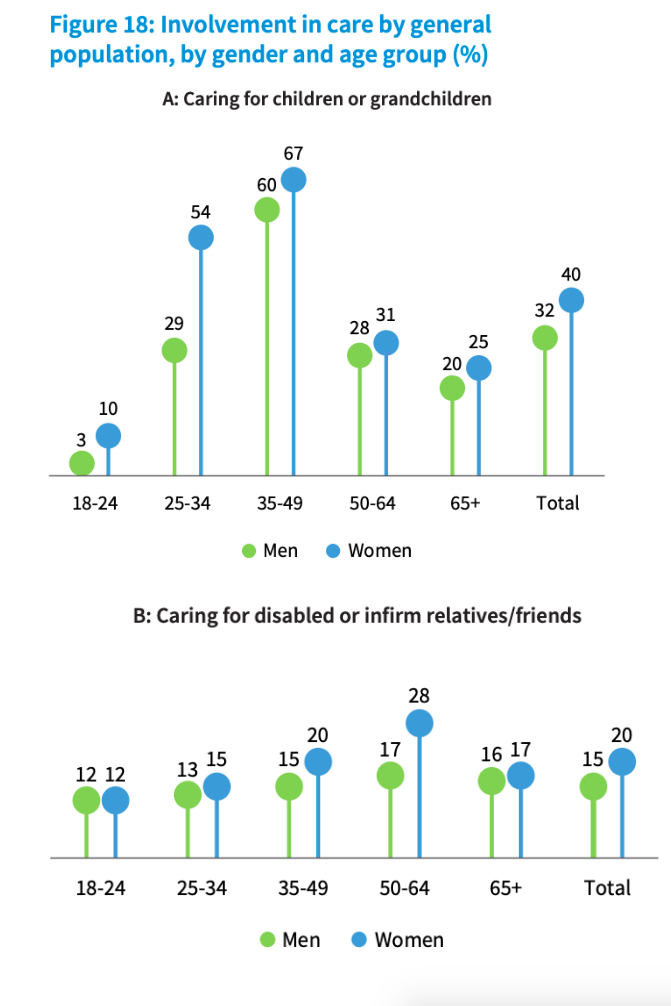

The most recent report from the European Survey on the Quality of life (2016) is telling about the long lasting persistence of gender patterns related to care work, still in 2020.

In general, women were more likely than men to report difficulties in combining work with care; 40% found this ‘rather’ or ‘very’ difficult compared with 33% of men. One significant difference was among those working full time (35 hours or more): in this group, 49% of women found it ‘rather’ or ‘very’ difficult compared with 35% of men.

Source: https://www.eurofound.europa.eu/sites/default/files/ef_publication/field_ef_document/ef1733en.pdf

The charts above show the percentage of women and men by age group who ticked the box for the specific care duties when asked about their involvement in caring activities: a gender gap is evident on involvement in childcare for the age group between 25-29 corresponding to average reproductive life, and in elderly people or infirm relatives or friends care for the age range between 50-64. Similar patterns are reflected in perceptions, as the study reports that “in general, women were more likely than men to report difficulties in combining work with care; 40% found this ‘rather’ or ‘very’ difficult compared with 33% of men. One significant difference was among those working full time (35 hours or more): in this group, 49% of women found it ‘rather’ or ‘very’ difficult compared with 35% of men”.

Women appear to continue delivering most of care work, whether it is about taking care of children or elderly or sick relatives, and in heterosexual couples, they tend to spend more time than their male counterparts in domestic tasks such as cleaning and cooking for the family. This in sharp contrast to a widespread argument stating that ‘modern’ families are much more balanced as far as the distribution of care work is concerned.

The capitalist society is actually built upon the division between the two realms of the productive paid work and the unpaid (so called) reproductive work (aimed at sustaining and reproducing the work force): feminist sociologists have elaborated a lot on the structural, gendered and intersectional inequalities implied in the articulation between productive and reproductive work, whereas the latter includes not only childbearing or domestic tasks but also emotional and sexual work. If on one side, families, communities, individuals are still unequally organizing the distribution of reproductive work, with women and migrant women in particular highly involved as care givers under heavy exploitation, on the other hand States/public authorities with their shrinking budgets are struggling to guarantee and expand provision of formal care services. Theorists and scholars are often emphasizing how reproductive work is a crucial site for changing the unsustainable economic model we live in (read the enlightening work by Silvia Federici on this).

When it comes to looking for solutions to the tensions and contradictions highlighted above, “work- life balance” is the proposed objective. The concept in itself it is widely used, although it has been criticized precisely for the risk it entails of hiding structural inequalities and contradictions and for the underlying ‘individualistic’ approach, and for implying that a 50/50 share between reproductive and productive work is something feasible, while it is not. This blog post illuminates part of the expert debate on work life balance as a contested concept while a more scholarly approach can be found in the papers by Eikhof and colleagues (2005) and by Ozbilgin and others (2007) with an intersectional and diversity perspective.

Work life balance tensions in academic and research institutions

Research and Higher Education institutions do not constitute an exception to most of the working places, although working in scientific knowledge production obviously means different working conditions, constraints and opportunities than manufacturing, or other compartments of the economy. A University career is still mostly shaped around a traditional ideal of the implicitly male and care burden-free scientists, intellectual totally focused on its own scientific endeavor. Organizational and institutional cultures in research organizations strongly resent of this ideal, where exclusive dedication to a rewarding work is reinforced by the values of contributing to knowledge production and education and a mission that academic workers feel they are committed to. This is obviously posing obstacles for women working in academic and research contexts and their career progression. At the same time, it leads also for men in similar career paths to reproduce and reinforce the male and childless normative model (read the paper from S. Wallee based on 70 interviews with fathers working at 4 different faculties).

Far from being a 9-to-5, 5 days per week job as someone might expect, being an academic brings with it an absence of boundaries between work and other areas of life and expectations of total commitment. Academic staff do not ‘clock-in’ 8 hours per day, therefore they mostly enjoy flexible working patterns, which under the already described prevailing organizational culture, comes at high risk of becoming overwork.

In addition, universities and research institutions are also impacted by changes of the neoliberal knowledge economy where funding from public budgets are reduced, fund raising is promoted from supranational funds and market related research sponsors, leading to less stable, and grant-based employment as well as more precarious working conditions in academia and research.

(on this particular topic an interesting podcast featuring lecturers and teachers from UK universities can be listened here and a thought provoking sociological case study from IT can be read here).

The speech bubbles of the picture above are drawn by selecting some of the quotes from in depth interviews carried out in a study on work life balance among early career researchers in the framework of the GARCIA Project: the quotes provide vivid examples of lived experiences from both men and women in both SSH and STEM Faculties in Belgium, Iceland, Italy, the Netherlands, Slovenia and Switzerland.

Sense of guilt, tensions in tasks’ distribution between partners, self justification for over work as a result of the passion and the motivation for knowledge production and authorship, perception of giving up career when opting for maternity are all expressed by respondents to the study (the full study, authored by Sanja Cukut Krilić, Majda Černič Istenič and Duska Knezevic Hocevar, is included as chapter 5 of the edited book by Annalisa Murgia and Barbara Poggio, titled Gender and Precarious research careers. A comparative analysis. Published in 2019 by Routledge, open access and accessible here).

https://www.youtube.com/watch?reload=9&v=DUT2WeiuKf8

Beside suffering from the contradictions of structural inequalities as far as care work is concerned and the expectations placed by male oriented institutional cultures, these video interviews with women researchers and professors, produced by the University of Southampton, show how individuals also constantly find strategies to cope, and even to push the blurred boundaries between work and care duties further, by stretching expected behaviors and rules, and sometimes, beyond bringing the work home, they even end up bringing the kids to Campus.

Good practices and inspiring examples from Research Institutions

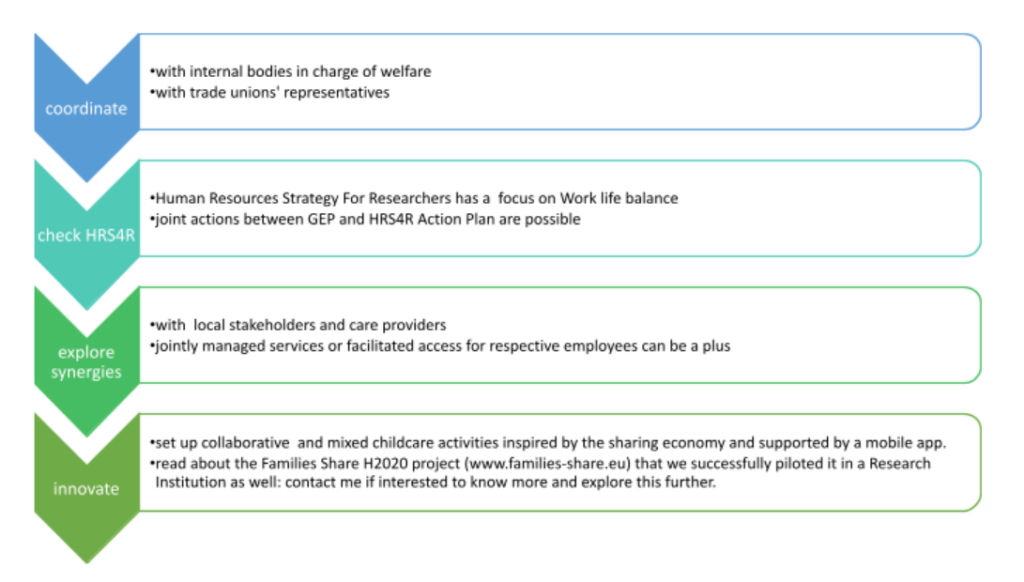

Designing actions to be included in a Gender Equality Plan to address work life balance challenges in research organizations needs to draw on internal evidence and the results from internal audits and assessment exploring conditions and perceptions of employees on the concerned issues. Also, national measures and provisions on parental/care related leaves are to be taken into account, while leveraging on services and opportunities available at the local level. Therefore, no “one- fix- for-all” approach is to be adopted, with the awareness of the primary importance to be attributed to the context and its specificities.

Usually, Universities committed to institutional change for gender equality, tend to work on different type of measures spanning from setting up on-campus childcare facilities or agreements with local care providers for discounted access to services for employees, running informational campaigns to increase the awareness of existing work life balance measures already in place, teleworking, support schemes when returning after parental leaves, measures for sustaining partners of newly hired researchers from abroad in relocating and finding a job, just to name a few examples.

If interested in some good examples, I can refer you to the dedicated section on work life balance of the EQUAL-IST Toolkit I was compiling last year, with several resource and cases.

Further tips for designing actions on work-life balance in GEPs

A case study of Good practices and gender sensitive teleworking policies in covid19 times

I would just close this lesson with an (unfortunately) as relevant as ever practice from TEAGASC. Agriculture and Food Development Authority in Ireland, partner of the Gender SMART H2020 Project on institutional change. Valerie Farrel from TEAGAS and the Gender SMART partners very kindly accepted to share with our GE Academy DOCC participants their in-progress experience on integrating gender sensitive teleworking practices as part of their Gender Equality Plan, triggered by the pandemic outbreak .

As the effects of Covid 19 outbreak will continue for long, it already emphasized gender inequalities in many respects and in research organizations as well: teleworking practices boosted across many sectors, lecturing and examining went on line, generating a paradigm shift in academic and research working practice. Effects will continue and will stay for long, so that it becomes of extreme importance mainstreaming a gender perspective in it: for those organizations active in designing Gender Equality Plans or Action in this moment, Valerie Farrell’s presentation could be a timely and inspiring learning opportunity.