Gender Equality Plans need to set up actions for change addressing the main challenges women face in academic and research institutions. This lesson aims at pointing at what is widely recognized to be one of the most hardcore challenges for institutional change: the poor presence of women at the top decision making levels of each institution. The article is structured along 3 main paragraphs and by reading it and consulting the linked multimedia resources you will learn the following:

- where we stand in terms of vertical segregation in Research and HE institutions in Europe

- what are the main features of the problem, the gendered discursive construction of academic and research leadership and the impact on women’s experiences once they manage to access those positions

- what measures can be taken to counteract such a challenge, and be included in Gender Equality Plans to achieve institutional change

Some facts and figures

We have all probably noted by visiting universities across several countries that one common interior design feature with highly symbolic value is the male and white dominated wall of fame that decorate the most prestigious meeting rooms or auditoriums with picture of the institution’s deans and rectors. This immediately works of as a reminder of the academic traditional organizational culture, and you might find yourself screening along the most recent frames by wondering “we might for sure find a few women in the last years”. Unfortunately, this is only seldom the case.

In the last few years, each year in the occasion of the International Women’s Day, the European University Association has been publishing updated figures on gender unbalances in the leadership of EU academic institutions on their website, drawing on figures from their members only.

The picture is quite discouraging as it reveals how in 2020, 15% of rectors in EUA member universities in 48 countries are female, compared to 85% being male. The situation varies across countries as the proportion of female rectors is above the average in 19 countries, and below in eight countries. Notably, 20 countries currently do not have any female rectors. The share of women vice rectors is double, and rises to 30%.

EUA has about 200 member universities mostly among middle and small universities so the picture is a partial one. For a more representative sample we can rely on less updated information from She Figures 2018, showing how back in 2017 women’s proportion among the “heads of universities or assimilated institutions accredited to deliver PhDs, amounted to 14.3% (21% in the broader pool of HEIs).

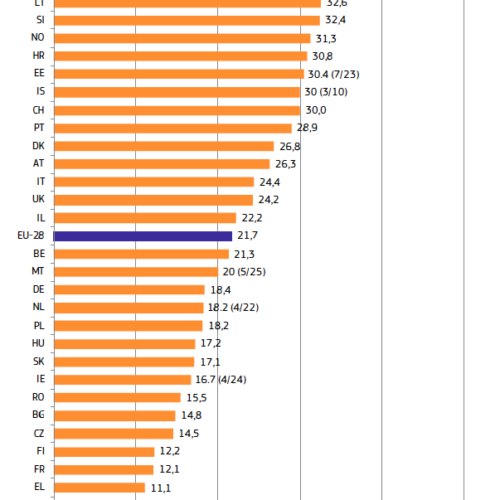

Proportion (%) of women among heads of institutions in the Higher Education Sector (HES), 2017 (Source : She Figures 2018)

Progress was detected in all countries when looking at the time period between 2014-2017 and a slowly increasing share of women leading Universities. Still, the issue of poor female representation in academic leadership is better understood if other problems are taken into account: there is a need to understand, for example, where women stand in terms of the entry pre-requisite for accessing a rectorate post (full professorship, also known as ‘grade A professorship’) and to what extent they are represented in other top management positions, such as Heads of Departments/Faculties but also Heads of Strategic Units like International Relations/Research/Communication/ Quality Assurance, etc.

Fine grained gender disaggregated data are not available at the EU level unfortunately to cover the entirety of the above mentioned positions, but again, from the She Figures study, we get a complete picture on 2 indicators, the share of women in Grade A positions, and the percentage of women among academic/research organizations’ boards members. ’

As far as full professorship and the highest levels of scientific careers, women constitute only 24% of grade A academic staff and 15% in STEM research organizations (12% in engineering and technology). Improvements were observed in all countries although at very different levels, and a more favourable situation noted for younger age full professors: in fact, according to SheFigures, “among grade A academic staff, women made up 36.2 % of staff less than 35 years old, 27.5 % of staff aged 35 to 44, 25.8 % of staff aged 45 to 54 and just 22.6 % of staff aged 55 or older”.

Overall, among all scientists, men are more than twice likely than women to progress to full professorship, given that while 7.4 % of women academic staff were at grade A, the corresponding proportion for men was 16.7 %.

These figures point at the so-called “vertical segregation” phenomenon in Academia and Research is so well known that also the ERAC (European Research Area Committee) spotlighted the need to increase female representation in leadership positions as one of the 3 main objectives for Priority 4 on Gender, together with Facilitating balanced recruitment and career progression for women in research and promoting the integration of gender as a dimension in scientific research content.

Female share of Grade A positions has, to this respect, become one of the “headline indicators” used when measuring national progress as far as the ERA priorities are concerned.

As reported in the ERA technical report

“the Headline indicator identified by ERAC for Priority 4 is the share of women in Grade A research positions in the higher education sector, as a percentage of all such research positions. Longitudinal analyses (in combination with the share of female PhD graduates) are suggested to measure the degree to which a glass ceiling still limits the professional advancement of women in research.

The “optimum” balance has been identified at around 50% (from 40 to 60%), because “a high share of females does not necessarily mean fair recruitment processes etc., but could reflect the unattractiveness of posts for men, for example because of low pay”. (European Commission, 2019a)

Communities of gender experts from Universities across all Europe gathered in the GenderAction project, have highlighted the limitations and reductionist effects of using this particular indicator to sum up where a country stands in terms of Gender Equality in research (GenderAction, 2019 ). It is a matter of fact, indeed, that if this is a multifaceted broader policy objective and the specific problem of vertical segregation is a complex one, which is not reflected by the share of women with Grade A positions only: statistics on leadership positions at different levels are missing, as already mentioned, and such complexity is revealed by the life experience of women in academia. Several recent qualitative studies keep highlighting this. In the following paragraph I’ll present some of the most interesting ones, up to my expert knowledge.

Leading academia and research: gender paradoxes and double binds

It has been made clear by feminist scholarly debates how a woman in a leading position within vertically segregated organizations happens to be perceived as “the other”, and this is due to gendered discursive constructions of leadership, whose features (behavioural patterns, dress codes, leadership styles) are typically ascribed to men. The paradox women leaders risk to get trapped in, is clearly related to the “double blame” or “double blind” of being perceived as inadequate both if they display masculinized behavioral codes (a woman in trousers type renouncing to her true self, too much aggressive) and if they try to display a ‘different’/’feminized’ leadership style (not serious enough, not firm enough). The blamers’ gender also counts, in this regard. For example, an ethnographic study of a UK Business School based on employees and colleagues reactions to a woman being appointed as a Dean showed how men voiced complaints out revealing how they felt endangered figuring it out the new course would be at their careers’ detriment. Even if the School was male dominated, meaningful comments such as “you need tits to get on around here” were recorded. On the opposite, women participating in the study revealed their concerns that the new Dean would not be especially supportive of women’s issues.

In the video interview below from INSEAD with Robin Ely, Professor of Organisational Behaviour at Harvard Business School, several mechanisms and structural barriers, including the double bind and trading off competence for likeability are illustrated, hindering the access and success of women in leadership: she refers to the business sector mostly but several of the obstacles traced by Robing Ely are also in present in academia, and multiple studies have proved it.

https://knowledge.insead.edu/leadership-organisations/unshackling-the-double-bind-2091

A recent research based on interviews with female vice-chancellors in Germany and the UK, confirmed how for women it is harder than men to get acceptance as leaders, as so called ‘old boys networks’ are in place. Getting increased visibility as leaders, seemed to pose women in the position of having their look, behavior under a magnifying lens and a perceived trend to be judged in any act which would differ from expectations because of their being women and not men. The same study pointed at other 2 aspects which are frequently addressed by the literature on gender and leadership across different sectors:

- women vice rectors agreed on the fact that a critical mass would be needed among professors and VCs in order to change a gendered culture at research institutions.

- there is a trend to appoint women in leadership positions in critical situations and when there is a need to show change towards a new course, something which can place an extra burden on women in such positions

- there is also some evidence that women tend to be more represented in leadership position in those institutions with less prestige/status

The literature and the examples on these topics are vast. ….

What actions could be designed and put in place to promote change?

3.1 Importance of policy measures and incentives at the national level

The issues reviewed in this lesson point at a multifaceted problem that cannot be easily tackled, and no one fix for all is viable. The national policy context is of major importance as the experience of some countries has shown: favorable and advanced national policies can incentivize (also financially) HEIs and RPOs to achieve change, while, on the other hand, it can happen that strong national policies impact on gender equality overall while not managing to successfully address the specific “hard-core” issue of under representation in top management positions.

In Germany the Federal Programme for Women Professors and the programme “Frauen an der Spitze” (“Women in the lead”) set up funds for female professorship.

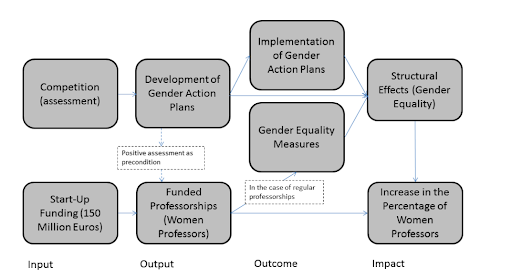

HEIs are requested to submit a Gender Equality Plan and if an external evaluation committee assesses it positively, the institutions can apply for start-up funding (for five years) for up to three tenured professorships filled by newly recruited women.

The picture above well represents the logic of the Programme and comes from a very interesting study from 2019 which has assessed the impact of the programme positively. It comes of course as part of a well-orchestrated set of measures taken at the Federal Government Level together with the Gender in Research Standards set up by the main National Research Funding body for Germany, the German Research Foundation (DF).

In the Netherlands the Westerdijk Professors (Westerdrijk-hoogleraren) “talent impulse” (NWO, the Ministry has provided HE institutions with five million euros for the appointment of 100 new female professors in 2018, to sustain the agreed European target of 25% female professors by 2020.

Switzerland: Since 2000, a programme called Equal Opportunity at Swiss Universities was put in place by the federal to make sure that 25% of all full and associate professors and 40% of all assistant professors were women by 2012. Progress was slow and the highest annual increase rate ever observed was 1.8% (in 2006). In 2016, 21.3% of full professors and 31.5% of assistant professors were women.

(Source: https://assets.gov.ie/24481/8ab03e5efb59451696caf1dbebe6fddc.pdf)

Austria has proceeded by including a quota rule for university bodies (rectorate, university council, senate and committees set up by the senate)m and appointment committees for full professors), centrally amending the Universities Act in 2002 with the regulation entering into effect in 2009. From an initial formulation aiming at 40% of the members of each body being women, it was changed to 50%. “In the year prior to its introduction, the share of female rectorate

members lay at 27%; in 2011, it had risen to 40%. In 2018, the share of women lay at almost 50% and 7 of the country’s 22 universities had female rectors. Austria was thus very successful in achieving the goal of integrating women into higher education management” (Wroblewski, 2019, p. 2).

3.2 Measures and actions at the institution level

Where national level incentivized initiatives are not in place, change can still be promoted in many different ways, and I would highlight a few inspirational practices to this regard.

Changing recruitment and promotion practices

The gender construction of leadership in academia and the bias which go with it is filtered into recruitment and appointment procedures and practices on the first place.

Panels assessing suitable candidates are often influenced by different types of bias even in contexts where merit and excellence should prevail. The video below simulates in a very effective way what gendered conversations recur in panels and the described situation refers also to leadership features.

Tips are also provided to handle evaluation panels in gender sensitive ways, that could contribute to positively influence on recruitment processes, including those giving access to leadership positions.

VIDEO on recruiting for a leadership position: from the CERCA Institute, in Spain

- Setting (target) quotas for the underrepresented gender

Reserved quotas in top positions for the under represented gender can be a mitigation tool, although typically exposed to opposition and controversial opinions. The history of this type of measures is linked to positive actions for women and minority groups in the US, and quotas have been frequently advocated against as unfair measures hindering meritocracy. A comprehensive account of the arguments in favour and against quotas to increase women’s representation in politics and beyond is drawn by Anne Phillips in Chapter 3 of her book “The Politics of Presence” (1998)

More recently, as a policy measures, quota have faced renewed consensus as the European Commission has proposed a Directive in 2012 on gender balance among non-executive directors of companies listed on stock exchange which has given rise to a lively debate and support from the European Parliament while also meeting opposition from some countries, leading to a halt in the legislative process (more can be read here).

This is actually part of a process initiated 2 decades ago already as the European Commission has started giving the good example as employer by setting a 40 % target for the under-represented sex in all their committees and expert groups, and later on a higher target of 50 % was set for Horizon 2020 advisory groups.

There are several devices which have become widespread and are featuring the history of “quotas” as policy measures also increasing their ‘acceptance’ rate:

- Formulating quotas as targets to tend towards in a given timespan, rather than strictly at a single hiring/recruitment procedure

- Addressing the underrepresented gender and not necessarily women only

- Stressing their nature as temporary measures

- Emphasizing the fact that procedures are in place to make sure the ‘quota’ candidates are equally qualified as all their competitors to contrast the widespread stereotype that quota hinder meritocracy

A recent report has been released by the EC and the Helsinki group on Gender in Research & Innovation providing guidance to Research Institutions to set targets to increase gender equality in research: such targets are deemed necessary to be applied to decision-making bodies, such as leading scientific and administrative boards, recruitment and promotion committees and evaluation panels, to achieve gender balance in leadership and decision-making positions.

The reading is interesting as it shed light on the fact that several countries have such measures in place already, often as part of national policy measures for all public bodies (and among those public University and publicly funded research institutes of course) but also via measures focused on Research and Higher Education more specifically. The Helsinki Group survey on whose findings the report is drawn, shows that quotas and targets are in place for boards most of the times, while evaluation and recruitment committees are less covered. Quotas or targets for gender in decision making, are in most cases set at 40 % of the under-represented sex.

Monitoring is highlighted as a main driving factor for effective implementation of quotas or targets according to the survey, mostly by way of sex-disaggregated statistical data collection.

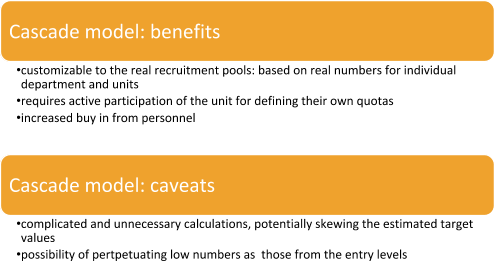

In recent years, a flexible ‘cascade’ model has also received attention and has raised interest: in this case, quotas are based on the percentage of women at the level immediately below for each type of position. They can be applied at all career levels, be mandated by a government, and associated with financial incentives for reaching the quota, and/or non-compliance sanctions.

The “Exploring quotas in academia” is a report from a study conducted by EMBO in collaboration with the Robert Bosch Stiftung, which has focused on this particular ‘softer’ way for implementing target quotas. The report shed light on both pros and cons of the model, recapped in the table below:

Finally, it is worth stressing a risk which is entailed in all type of targets/quotas when applied to recruitment panels and committees in particular: a work overload can be generated for the few women in high positions who start getting requests to sit on several committees. For scientists and academics in particular, this can result in harm to their research commitment. A mitigating measure can consist of relieving them from administrative duties and/or providing extra support for research duties.

Promoting actions to support individual women with leadership potential (and will)

Training on leadership and mentorship programmes are often referred to as viable measures to better equip women who are considering to set their career goals as high as to the top management and leadership positions. As explained already, being perceived as ‘others’ in such positions, and experiencing the related contrasting expectations by colleagues, are common experiences for women in leadership and therefore supporting initiatives could prove to be useful. Still, training and mentoring women are and can be identified as actions aiming at “fixing the women” rather than the institution, therefore relying on (or conveying) an implicit assumption that women “lack” the needed skills, expertise and motivation.

Therefore, when preparing and implementing a Gender Equality Plan, it is important that they are designed and implemented careful paying attention to the following:

- Make sure they are not the only action foreseen to address gender unbalances in decision making positions within the GEP. Take inspiration from other type of measures highlighted in this chapter as well.

- Devise an internal communication campaign that frames the activity to counteract as much as possible the idea that women are in need of being skilled

- Complement training to women with training targeting everybody to raise the awareness of gendered constructions of leadership in academia more broadly

- Avoid as much as possible essentializing definitions of female/feminine and masculine leadership styles

A good example is the context and evidence based approach to training on leadership in academia presented by Schmid and others in their paper from 2017, titled Unlocking women’s leadership potential: the authors share reflections from the implementation and evaluation of the course they have piloted, and targeted at post doc research fellows and associate professors from three German Universities, aspiring to achieve top management positions. The courses’ design adopted a self-directed learning approach allowing women to unveil the bias they were perceiving themselves about supposedly contrasting academic identities (teaching, researching, administering and managing), even the multiple forms of discrimination they were facing for those having migrant backgrounds, voicing their frustrations, and set up their own career development strategies.

As a very final remark, I would add an extra tip as far as developing training/mentoring initiatives on this topic are concerned: if we want to fully exploit the transformative potential of such learning opportunities for women, it is important also to train perspective leaders to become agents of change themselves. A training or mentoring for women on leadership should always include sessions or modules on how to promote change at the institution that you will (or have managed to) lead: in fact, it has been proven how the presence of women leaders per se, only partially related to an increased promotion of institutional change measures. Angela Wroblewski in her recent study on women in rectorates in Austria titled Women in Higher Education Management: Agents for Cultural and Structural Change? reflects precisely on this and recalls how setting up goals on gender equality and gender competence as a qualification criteria for all rectors and vice rectors would be necessary to tap on the potential of more women leaders, so that they actively promote institutional change themselves, once in power.