Introduction: What is gender-sensitive teaching?

The fact that there are as many female as male students in higher education does not make university teaching automatically gender sensitive.

“Gender-sensitive teaching pays attention to gender differences both in creating syllabus and in class conduct. It means introducing students to the gender dimension of the presented contents, including publications that take gender-sensitive approach into the courses readings, and giving homework assignments that demand from students to think about gender dimension of the subject.”

Garcia Project Toolkit

In this lesson we will focus on:

● Knowledge transfer: a body of scientific knowledge and methods are taught from teachers to learners, history of sciences included

● Knowledge critique and creation: critical thinking and reflexivity as central abilities to be nurtured and at least in principle, contribute to further knowledge creation

● Human interaction, and power relations (teacher/students; students/students) ● Assessment and evaluation procedures (testing and examination)

Gender in curricula

The focus on curricula is very important.

Gender equality is not only seen as promoting equal treatment and equal opportunities, but the gender equality goal is also expressed in all curricula in all levels of education.

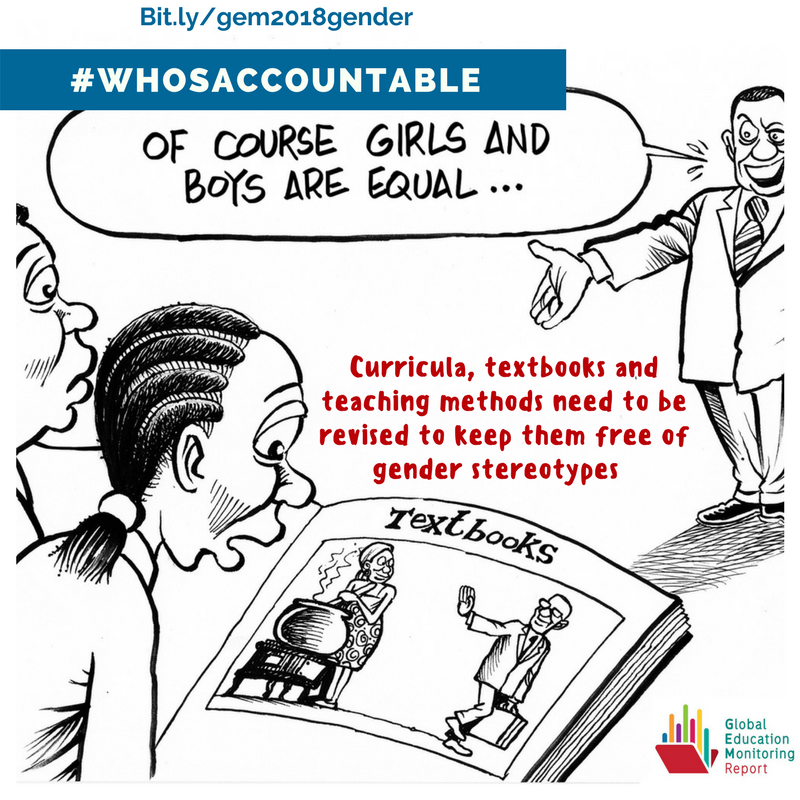

Gender blind curricula hold the potential to enhance the inequality of opportunities existing in society, to address one gender more than the other, to generate unequal success opportunities, and even to strengthen the already existing gender role stereotypes.

UNESCO (2011) has issued several recommendations that should be taken into account in all publications (curricula and textbooks, learning materials, legislation on education).

Some of them are:

● All publications should employ gender neutral and gender inclusive language; ● All images used (such as photographs, illustrations or even book covers) should be gender balanced (equal representation of men and women) and avoid promoting gender stereotypes;

● All images illustrating active roles of women/girls should be encouraged in order to contradict female invisibility in educational materials;

“The use of inclusive language is important in terms of promoting gender equality. The use of male centred references in official documents and text books (in many languages the masculine works as a universal reference) needs to be addressed if we wish promoting gender equality. It is important to be aware that language does not only reflect the way people think: it also shapes the way people think. Using male references only (words and expressions that imply that women are included/inferior in/to men) is perpetuating this assumption of invisibility/inferiority and it tends to become part of people’s mentality. Research has shown that the use of gender free language is very important in terms of decreasing gender stereotypes and promoting gender equality.”

(Maria Esteves , 2018. GENDER EQUALITY IN EDUCATION: A CHALLENGE FOR POLICY MAKERS, PEOPLE: International Journal of Social Sciences)

Gender in curricula: focus on science

Traditionally, in the more abstract and theoretical fields of science, the introduction of a gender perspective has been ignored, on the assumption that scientific concepts, theories and methods are (gender) neutral. However, the language, metaphors, analogies and iconography used as a support may offer a partial view of reality and reinforce gender stereotypes. It should be emphasised, moreover, that in the applied use of science in fields like medicine, engineering and social sciences, where human subjects matter and whose results or derived applications affect human beings directly, gender biases are common.

Feminist epistemology scholars studying the history of science have widely and intensively argued against the supposed ‘neutrality’ of science, and showed how science in the making has been built around visions of objectivity, a strong positivist ethos and belief in a single/individual source of knowledge creation distinct and not implicated in the knowledge object which have marked gender (and intersectional) features: works from Sandra Harding, Fox Keller and Barbara McClintock and many others in the ‘80s and 90’s have provided examples of such implications in scientific fields such as quantum physics, biological sciences and genetics (see: Evelin Fox Keller, Reflections on Gender and Science, 1985, Evelyn Fox Keller & Benoit B. Mandelbrot, A feeling for the organism: the work and life of Barbara McClintock, 1984; Evelyn Fox Keller, Making Sense of Life: Explaining Biological Development with Models, Metaphors, and Machines, 2002. Sandra Harding, “Rethinking Standpoint Epistemology: What Is ‘Strong Objectivity’?” in Feminist Epistemologies, ed. Linda Alcoff and Elizabeth Potter, 1993).

The origins of the present emphasis on taking the gender dimension into account in scientific research relies precisely in that body of knowledge, which was pointing at how science has been traditionally shaped both by excluding women and disadvantaged subjects from scientific inquiry, and rendering gendered power relations invisible or even crafting theories of social phenomena which reinforced- reproduced gendered social hierarchies.

The entry of women scientists and feminist/gender scholars into different academic disciplines has generated new research questions, methods, theories, and research results.

Accordingly, the core element of “engendering” teaching curricula, would be to include contributions from feminist critics of science into the scientific content of courses or to mainstream reference to them whenever epistemological aspects are treated or the history of science is scoped.

Secondly, it is important to show concrete and discipline-specific cases of how a gender dimension can be embedded into scientific research: it would be important both to plan and design dedicated lessons to these topics and mainstream references to them across the other lessons whenever relevant.

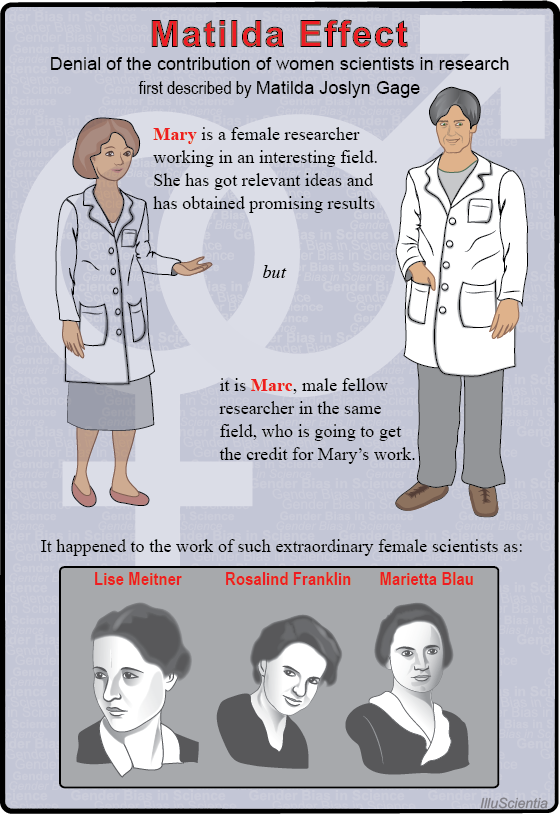

Highlight and value women’s scientists contribution to the history of sciences is another, relatively simple, way to enhance gender sensitivity of a science curriculum. A bias against the recognition of women scientists has been detected, with their work often being undervalued or sometimes attributed to male colleagues. This bias was called the “Matilda effect” by science historian Margaret W. Rossiter in 1993, upon the name of suffragist and abolitionist Matilda Joslyn Gage (1826–98) who first coined the term in her essay, “Woman as Inventor”

(creative commons from https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Matilda_effect)

There are plenty of examples of women scientists made invisible when awarding prestigious science prizes, and in textbooks. Every effort should be made to avoid and combat the reproduction of gender stereotypes and bias in university education and to raise students’ awareness of non-discrimination in their future careers.

“Physics textbooks are notorious for giving the impression that the history of physics has been a linear development of great discoveries made by solitary gentlemen scientists (…). Unsurprisingly, people regard themselves as less able to contribute to an enterprise when the history of that enterprise does not include members of their group (…). All of these different factors lead to the expectation that successful physicists must be solitary, male geniuses, who construct new theories and knowledge by the sheer force of their own personal intellects.

Many different types of individuals, most importantly (though not exclusively), women, are simply not expected sources of physics knowledge. The internalisation of those cognitive expectations leads to increased (implicit) discrimination, reduced participation, and less chance for success (…). The internalisation of these cognitive expectations not only excludes people from the domain of physics, but also can potentially eliminate various ways of knowing and knowledge construction. If knowledge is expected to be the product of a solitary genius, (…) [these expectations] also belie the reality that modern-day physics is actually practised and constructed by communities of scientists working in close collaboration with each other (…)”.

Maralee Harrell (2016), “On the Possibility of Feminist Philosophy of Physics”. In: Maria Cristina Amoretti and Nicla Vassallo (eds) Meta-Philosophical Reflection on Feminist Philosophies of Science. Boston Studies in the Philosophy and History of Science, vol. 317. Springer, Cham (pp. 24-25).

Unconscious bias in the classroom: teacher-pupils and peer-to-peers interaction

However, after reflecting on the construction of curricula, it is necessary to reflect not only on the methods of teaching, but also on the interaction within the class. The development of the curriculum to address gender inequality is not in fact an isolated aspect of teaching practice.

Equity will not be achieved for example if girls are discouraged from talking, or if boys absorb a disproportionate amount of energy from teachers, or if the physical environment does not support equal access to education.

Research by the Institute of Physics (IOP) suggests that boys tend to dominate in the classroom, answering more questions and getting more of the teacher’s attention, usually without the teacher being aware of any imbalance.

In the classroom, unconscious bias can manifest itself in teacher–learner interactions. For example, teachers may be more likely to praise girls for being well behaved, while boys are more likely to be praised for their ideas and understanding. A disruptive girl may be treated differently to a boy who exhibits similar behaviour. These expectations can be harmful to both groups. Girls may learn to be compliant and not take risks, while boys may opt out of education if understanding does not come readily.

What is unconscious bias?

We can minimise the harmful effects of gender imbalance and gender stereotyping by understanding unconscious bias. Unconscious bias refers to a bias that we are unaware of, which happens outside of our control. Our assumptions are influenced by our background, personal experiences, social stereotypes and cultural context. Unconscious bias arises because our brains have to process vast amounts of information every second. In order to avoid being overwhelmed, our brains have to make assumptions based on previous experience and find patterns to enable fast decisions. These assumptions however tend to be based on simple characterisation of people such as their age, race or gender. They are communicated through micro-messages such as body language and choice of words. They are more likely to manifest when we are stressed or tired, and can be problematic if they affect our beliefs and treatment of others. Everyone has unconscious biases. These biases do not necessarily make a person ageist, sexist or racist. An individual can be unconsciously influenced by a stereotype even if they do not rationally subscribe to the limitations implied by the stereotype.

https://www.iop.org/education/teacher/support/girls_physics/resources/file_70035.p df

Teachers, like all of us, have unconscious biases, which can influence the learning experience of different groups of students. It therefore becomes central to train teachers, raise awareness of unconscious biases and allow teachers to reflect on their own practice.

Targeted training can also help teachers deal with sexist and sexual comments or inappropriate behavior.

Gender- and diversity-conscious teaching

So what is the right approach to teaching regardless of the discipline? It is about developing a method of teaching that is aware of gender and diversity.

The NCTE (National Council of Teachers in English) in its guidelines on gender and language provides clear advice on the creation of the curricula:

“Create lessons and materials that discuss gender as a spectrum, and that include a range of gender identities, rather than inadvertently perpetuating a binary concept of gender or excluding transgender students through curricular and instructional choices.”

https://ncte.org/statement/genderfairuseoflang/

Maria Helena Esteves, in her essay GENDER EQUALITY IN EDUCATION: A CHALLENGE FOR POLICY MAKERS, goes into detail, giving clear examples:

● Seize and create classroom opportunities to discuss and challenge gender assumptions, particularly binary assumptions about gender.

● Avoid assuming binary gender identities by designing activities that divide the class into boys and girls.

● Avoid assuming binary gender identities when assigning readers or roles for texts being read aloud or performed.

● When facilitating discussions of the impact of gender identity on personal, social, or political experience, move beyond binary terms that compare and contrast the experiences of women and men to ensure that such explorations consider experiences of those with nonbinary identities as well.

● Understand that a student’s gender identity may impact their engagement with certain texts and/or participation in certain conversations.

Maria Helena Esteves

According to the Freie Universität Berlin:

“Gender- and diversity-conscious teaching is all about improving teaching. It’s not about casting aside existing criteria for good teaching or reinventing them altogether; instead, it aims to add to and refine existing criteria by raising specific considerations.”

https://www.genderdiversitylehre.fu-berlin.de/en/toolbox/teaching-methods/didactic-p rinciples/index.html

To learn more about this concept, watch the video of the Freie Universität Berlin entitled: “Gender- and diversity-conscious teaching”

The Freie Universität Berlin identifies two didactic principles that are especially helpful for paying attention to gender and diversity in teaching: a variety of methods and engaging students. These two principles are closely linked and together constitute a small revolution in teaching methods.

Using a variety of Methods

Variety of methods entails not designing every session of a course identically, but instead using various methods. Not all students do well with the same learning methods. By using a variety of methods, it is more likely that everyone will find their own way to make decent progress.

Read more: https://www.genderdiversitylehre.fu-berlin.de/en/toolbox/teaching-methods/didactic -principles/index.html

Students engagement

When we think of student engagement in learning activities, it is often convenient to understand engagement with an activity as being represented by good behavior (i.e. behavioral engagement), positive feelings (i.e. emotional engagement), and, above all, student thinking (i.e. cognitive engagement) (Fredricks, 2014). This is because students may be behaviorally and/or emotionally invested in a given activity without actually exerting the necessary mental effort to understand and master the knowledge, craft, or skill that the activity promotes.

Read more:

https://www.edutopia.org/blog/golden-rules-for-engaging-students-nicolas-pino-jam es

Gender conscious language

Language is central in all teaching routines… It shapes relations in the classroom, both as spoken language and written text or as body language. Language builds social reality and its norms and in interaction between people. Young people in particular build their self perception and the perception of what they might or might not be able to achieve also through language.

“In most European languages, plural masculine form is often used to refer to both men and women – when referring to unknown individuals, officials’ titles, names of the profession etc. Use of feminine form, or interchanging masculine and feminine ones, makes women more visible in both life and science. Even more, using feminine forms may remind you of the potential gender dimension in your research, which you might have overseen.”

Garcia Toolkit https://eige.europa.eu/sites/default/files/garcia_toolkit_gender_research_teaching.pdf

According to the Toolbox from the Free University in Berlin, there are three main good reasons to use gender and diversity conscious language:

1. “It creates more visibility: by recognizing and verbally illustrating the accomplishments of all university members.

2. It addressed everyone: by addressing students and other university members in such a way that all feel recognized and valued.

3. It avoids stereotypical representation and discrimination: Instead of language that hurts, degrades or exoticizes people, employing language that values and recognizes them”.

There are ways to practice gender-inclusive language beyond just respecting gender-neutral pronouns. For example, by not using a word ending in “-man” as the default phrase for a descriptor, we can normalize the idea that anyone can perform a job, regardless of their gender identity.

In an article on Teen Vogue you will find interesting examples including:

● Folks, folx, or everybody instead of guys or ladies/gentleman ● Humankind instead of mankind

● People instead of man/men

● Members of Congress instead of congressmen

● Councilperson instead of councilman/councilwoman

● Parent or sibling instead of mother/father

● Child instead of son/daughter

● Sibling instead of sister/brother

● Nibling instead of niece/nephew

● Partner, significant other, or spouse instead of girlfriend/boyfriend or wife/husband

● Salesperson or sales representative instead of salesman/saleswoman ● Server instead of waiter/waitress

● Firefighter instead of fireman

Assessment: examination

A final aspect to be taken into account: evaluation practices are found to be affected by bias in many different ways. Test anxiety (a feeling of agitation or distress before or during an exam) is a proven gendered phenomenon.

“Test anxiety has detrimental effects on the academic performance of many university students. Moreover, female students usually report higher levels of test anxiety than do their male peers…..Compared with their male counterparts, female students reported higher levels of test, math, and trait anxiety, as well as greater expected anxiety in three of the four test situations considered. However, females did not show lower academic achievement than male students in either the open-question or the multiple-choice exams. These results are discussed in terms of gender differences in socialization patterns and coping styles.”

Núñez-Peña M Suárez-Pellicioni M. Bono R. (2015). Gender Differences in Test Anxiety and Their Impact on Higher Education Students’ Academic Achievement.

GRADING WITH TEACHER BIAS

An education study done in Israel showed that gender bias also affects how teachers grade their students.

“In the experiment, the researchers had classroom teachers, as well as external teachers, grade the same set of math tests completed by both girls and boys; they found that classroom teachers systematically gave their female students lower grades than the external teachers did. The only difference between the classroom teachers and the external teachers was that the external teachers graded blindly with respect to gender.

What’s even more striking is that the same girls who were scored unfairly in sixth grade ended up pursuing fewer high-level STEM courses in high school. As one commentator on the study pointed out, most of the teachers involved in the study were female, so “it’s hard to imagine that these teachers actually have conscious animosity toward the girls in their classroom.” It’s an unconscious bias that caused them to treat their female students unfairly when it came to math and science—perhaps the same way their own teachers treated them.” https://www.thegraidenetwork.com/blog-all/2018/8/1/teacher-bias-the-elephant-in-the -classroom

If you want to discover more about inclusive teaching, here you find 10 tips for teachers developed by the IOP Institute for Physics:

https://beta.iop.org/sites/default/files/2019-07/IGB-10-tips-whole-school-poster.pdf

An useful classroom interactions self-evaluation template

https://www.iop.org/education/teacher/support/girls_physics/resources/file_68641.pdf

How can we integrate gender perspective into university teaching? In this video the Universitat Central de Catalunya shows how to incorporate gender perspective into university teaching

Literature on the subject and recommended books

There is abundant literature on these issues, since the 70s and mostly linked to critical education studies and pedagogies. Cross Disciplinary approaches include educational studies, pedagogy, social psychology and sociology of education. These are 2 examples of more recent books

Henderson, F. E., Gender Pedagogy

When addressed in its full reactive potential, gender has a tendency to unfix the reassuring certainties of education and academia. Gender pedagogy unfolds as an account of teaching gender learning that is rooted in Derrida’s concept of the ‘trace’, reflecting the unfixing properties of gender and even shaking up academic knowledge production.

Case, K.A. (2020) Intersectional Pedagogy. Complicating Identity and Social Justice.

Intersectional Pedagogy explores best practices for effective teaching and learning about intersections of identity as informed by intersectional theory. Formatted in three easy-to-follow sections, this collection explores the pedagogy of intersectionality to address lived experiences that result from privileged and oppressed identities. After an initial overview of intersectional foundations and theory, the collection offers classroom strategies and approaches for teaching and learning about intersectionality and social justice. With contributions from scholars in education, psychology, sociology and women’s studies, Intersectional Pedagogy includes a range of disciplinary perspectives and evidence-based pedagogy.

References

https://www.globalpartnership.org/sites/default/files/2016-11-gpe-policy-brief-gender equality.pdf

https://www.wus-austria.org/files/docs/Publications/guidelines_gender_fair_curriculu m_development.pdf

https://www.iiste.org/Journals/index.php/JEP/article/viewFile/16707/17071 https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000261593/PDF/261593eng.pdf.multi