In this lesson you will have the opportunity to learn about the terminology in use to frame complex and multifaceted phenomena such as gender based violence and sexual harassment which can affect both relations among employees, peer relations among students and teachers/students relations.

We aim at providing you with the tools to counteract a widespread argument which tends to deny the existence of the problem in Higher Education by simply stating that “as we don’t have rape or major criminal offence‘s cases these issues are not relevant for our institution”. You will also know about concrete experiences and cases of Universities that took action to contrast gender based violence and sexual harassment. These can inspire you to include specific actions in your Gender Equality Plans aimed at tackling these problems, always considering that whatever practice cannot simply be transferred as such but has to be designed and developed starting from its specific institutional context.

Key concepts: gender based violence and sexual harassment

Gender-based violence and violence against women are terms that are often used interchangeably as it has been widely acknowledged that most gender-based violence is inflicted on women and girls, by men. However, using the ‘gender-based’ aspect is important as it highlights the fact that many forms of violence against women are rooted in power inequalities between women and men: bringing the ‘gender’ concept into the picture, helps us disclosing a set of complex dynamics as we , refer to gender as a social construct with its cultural norms and expectations enshrined in socio-economic inequalities. We can rely on the two following definitions from important international institutions. «Gender-based violence is violence directed against a person because of their gender. Both women and men experience gender-based violence but the majority of victims are women and girls.” (EIGE)

«Sex and Gender-based violence is a violation of human rights. It denies the human dignity of the individual and hurts human development.» (UNHCR)

As Gender Based Violence tends to be typically identified with serious criminal offence and/or rape, sexual harassment is a an important concept/frame to be used to address the issue in organizations and working places, whereas the immediate reaction could be denial of the problem as such. The EIGE’s definition below clearly explains how sexual harassment has to do with intimidating, offensive behaviour at large, including sexist jokes, “lighter” forms of unwanted attention and invasive approaches such as touching more or less disguised by ‘friendly’ manners.

“Any form of unwanted verbal, non-verbal or physical conduct of a sexual nature occurs, with the purpose or effect of violating the dignity of a person, in particular when creating an intimidating, hostile, degrading, humiliating or offensive environment.”

(EIGE- Glossary)

However, it is also important to highlight the frequent risk that sexual harassment is reduced to ‘bad behaviour’ perpetuating the misunderstanding that it is ‘merely’ inappropriate/uneducated and uncomfortable, not necessarily illegal and enforceable by law.

Feminist movements and international campaigns have recently increased the awareness on these issues across several sectors and industries, starting with the most popular cinema and creative media and the #metoo movement, to spread to the academic world and the EPWS (European Platform of Women Scientists) campaign #wetoo in science in 2018.

The international legal framework adopts a comprehensive scope to gender based violence, including sexual harassment

In the last decades of the 20th century there was a general consensus in the international community that the rights of women were not adequately protected by the existing international framework and the Universal Declaration of Human rights .

Notably, as a result, in 1979 the United Nations General Assembly adopted the Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination Against Women (CEDAW), which is considered the women’s international bill of rights and the most comprehensive set of rules relating to non-discrimination and equality. Complementing CEDAW is the Declaration on the Elimination of Violence against Women (DEVAW), 1993, which provides a comprehensive definition of violence against women as well as principles and standards that are key to addressing this global problem. More recently, in Europe, the Istanbul Convention, coming into force in 2014 and approved by the European Parliament in 2017, which explicitly uses a broad definition of violence, including sexual harassment.

Referring to such international legal frameworks, and their ratifying/signing (or not, as far as the Istanbul Convention, for example ) is very important when arguing against resistances or denial of the problem.

In the next paragraphs we’ll look closer into the multifaceted forms of GBV (Gender Based Violence).

Forms of violence

Gender-based violence is enacted under many different manifestations. These different forms are not mutually exclusive and multiple incidences of violence can be happening at once and reinforcing each other. Inequalities experienced by a person related to their race, (dis)ability, age, social class, religion, sexuality can also drive acts of violence. This means that while women face violence and discrimination based on gender, some women experience multiple and interlocking forms of violence, and that an intersectional approach to GBV is crucial to understand and address their problem.

- Physical violence

Any act which causes physical harm as a result of unlawful physical force. Physical violence can take the form of, among others, serious and minor assault, deprivation of liberty and manslaughter.

- Sexual violence

Any sexual act performed on an individual without their consent. Sexual violence can take the form of rape or sexual assault.

- Psychological violence

Any act which causes psychological harm to an individual. Psychological violence can take the form of, for example, coercion, defamation, verbal insult or harassment.

- Economic violence

Any act or behaviour which causes economic harm to an individual. Economic violence can take the form of, for example, implicitly or explicitly threatening someone of firing her/him if sexist jokes or sexual abuse are not accepted

Overall, we can say that GBV is an abuse of POWER. Although power can be used for good purposes, and not all those who have power abuse it, power can be used to dominate, to marginalize, to force other persons to act against their will and to impose restrictions in others people’s lives. Power is directly linked to choice, so persons with little power – such as children, many women, especially those who experience multiple discriminations (by age, migrant background, class, disability or gender identity) – have fewer choices and are more vulnerable to GBV. As mentioned, an intersectional lenses are needed, and a one-fix-all approach cannot work. Research from the US, reported in this article from the Harvard Business Review, tells us how when we go beyond gender the picture gets much more complicated and the stereotypical image of the victim (young female) and the perpetrator (senior male), both white or non racially identified, ends up blurring: the study found that on the surveyed sample, for example that Asian women tended to be harassed by much more junior male colleagues than white women, that more than one out of five black men had been sexually harassed by a colleague, compared to 13% of white men, and 85% of those black male victims had been harassed by a woman.

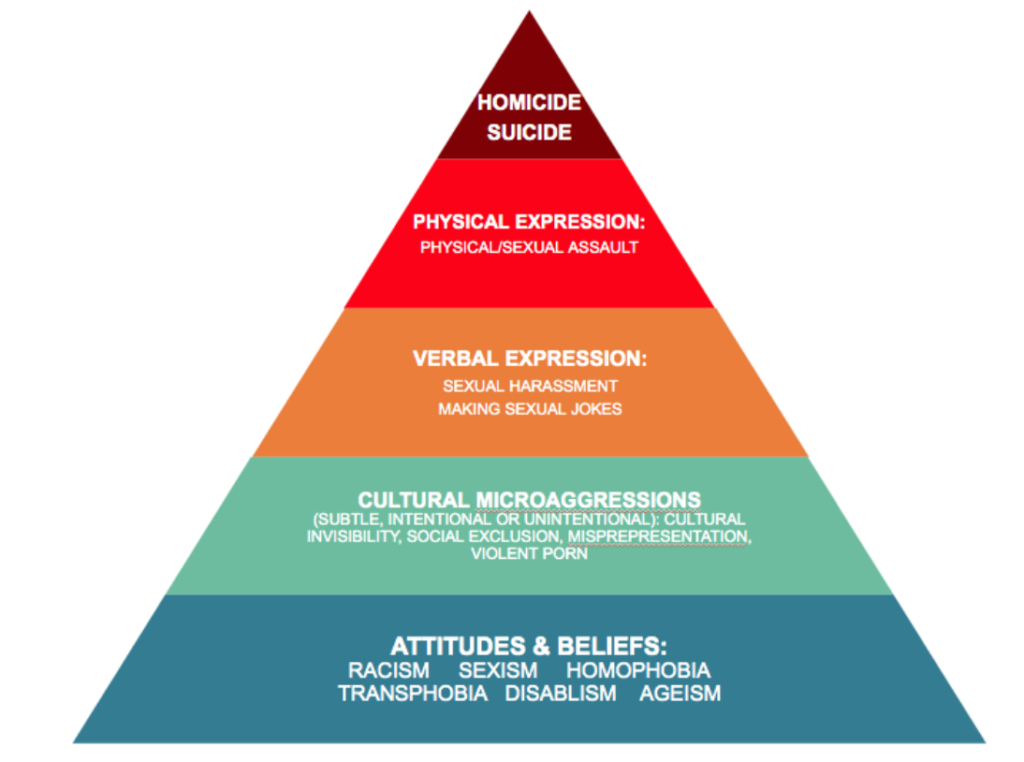

The pyramid of discrimination and violence

Source: «The intervention Initiative» University of Exeter

In order to contrast the entrenched assumption that sexual harassment or even sexual violence are a sort of an inevitable fact of life, we might stress the widespread ‘social acceptance’ aspect featuring GBV. The graphic representation and metaphor of a ‘pyramid of violence’ is useful to frame the abuse as a continuum – the further up to the pyramid’s top,, the less socially acceptable behaviours are. We report below the definitions of each single level as presented by the University of Exeter Intervention Initiative Project:

“Stage 1: Beliefs and attitudes: sexual violence is not usually something that an offender simply chooses to commit impulsively out of the blue. Sexual violence, like other forms of violence directed at someone because of their identity, starts with established attitudes and beliefs about other people, whether or not those attitudes or beliefs make sense. These include prejudices such as racism, sexism, transphobia. As offenders cultivate these beliefs through exposure and repeated reinforcement by those around them, they strengthen their dogmatic belief that certain types of people are simply not equal to them, moving them up the pyramid.

Stage 2: Microaggressions: called ‘microaggressions’ not because they are insignificant but because they are all around and normalised as part of our culture, these things represent the daily indignities experienced by people who have less power in society. For example a workplace that only has pictures of Caucasians – white people – on the walls.

Stage 3: Verbal expression: soon, people with prejudiced attitudes begin verbally expressing these feelings of difference and superiority, testing the waters with jokes or stereotypical statements about others; even beginning to harass others, or boast about times they verbally or physically marginalised others. Once this type of behaviour begins, it may remain at this level or there may be an internalisation of a grossly invalid sense of entitlement and offenders begin to normalise the dehumanisation of others – they actually begin to treat others as less than human.

Stage 4: physical expression This is where sexual violence happens. As offenders move up through the pyramid, they feed off the power they have gained. This is where a sense of sexual entitlement can begin to manifest itself as sexual violence. Offenders believe that it is their right and within their power to use sex as a means to control the individuals they do not see as equals. They can often justify the pain they inflict on others because they believe the victim/survivor has done something to deserve the assault. They do not feel responsible for the crime they’ve committed, and they may not even recognise their actions as an assault.”

GBV: main roles

The term “victim” is usually used in the legal fields. Early programmes to address sexual violence in conflict and displacement used this term. Today “survivor” is more commonly used and is preferred to “victim” especially when referred to assault and rape in psychological and social support sectors because it implies resilience.

Potential perpetrators can be intimate partners, family members, close relatives and friends, influential community members who are in positions of authority, security forces and soldiers including peacekeepers, humanitarian workers, institutions, as well as persons or entities who are unknown to the survivor.Most acts of GBV are perpetrated by someone known to the survivor.

A key role not to be disregarded is the bystander. A bystander is a person who witnesses an event. We are all bystanders, all the time.

Who is he/she?:

- Someone who is not directly involved in the event (not a victim or perpetrator)

- Witnesses a situation

Gender-based violence: how widespread?

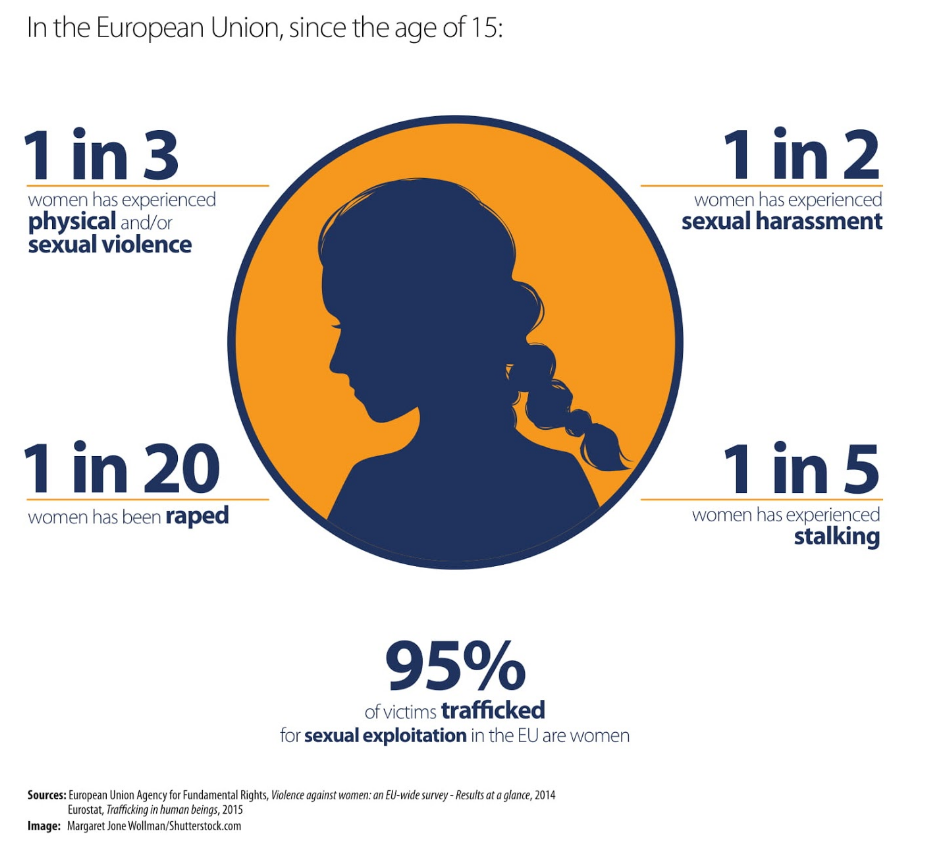

According to survey conducted in 2014 by the European Union Agency for Fundamental rights, «Violence against women: an EU-wide survey – results at a glance», in the EU since the age of 15, 1 every 3 women has experienced physical and/or sexual violence, 1 in 2 women has experienced sexual harassment, 1 every 20 women has been raped, 1 in 5 women has experienced stalking, while the 95% of victims of sexual exploitation in EU are women.

As anticipated, the Global #MeToo movement has contributed to raise the awareness of the problem and opening the Pandora box of private experiences bringing the attention to the public sphere.

Source: https://eige.europa.eu/gender-based-violence/what-is-gender-based-violence

Gender based violence: a biased perception

The European Commission Special Eurobarometer 449: Gender-based violence (2016) assessed the perceptions of EU citizens about gender-based violence. The survey covered:

1) opinions about and attitudes towards gender-based violence

2) perceptions of the prevalence of domestic violence and sexual harassment

3) whether a range of acts of gender-based violence are wrong and are, or should be, illegal.

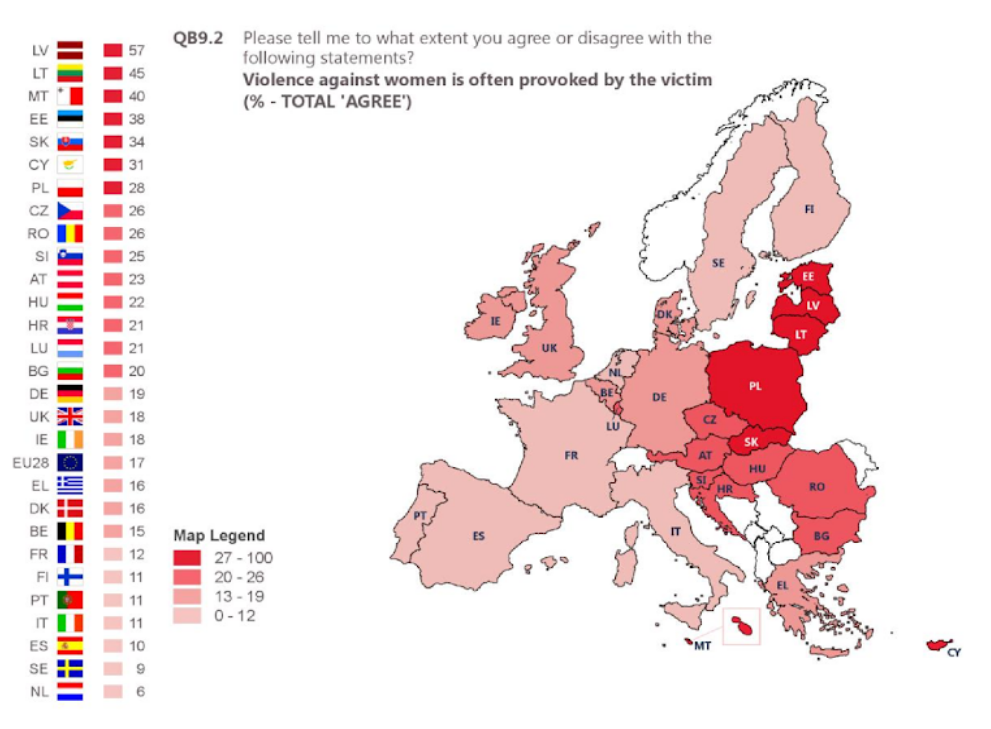

20% of the respondents agreed that violence against women is often provoked by the victim.

The more intense is the color, the higher is the % of people agreeing that violence is provoked by the victim.

This shows how there is a serious work to be done to increase awareness and overcome bias about how the phenomenon is perceived, as biases perceptions influence behaviours of all the involved parties, and on this specific aspects could have a role in discouraging reporting of harassment/violence.

In the next paragraphs, we are going to zoom into the world of Higher Education and Research Institutions, to understand how GBV phenomena are representing a challenge also in such environments and working places, and how they can be challenged..

GBV in Higher Education: results from the Gendercrime project

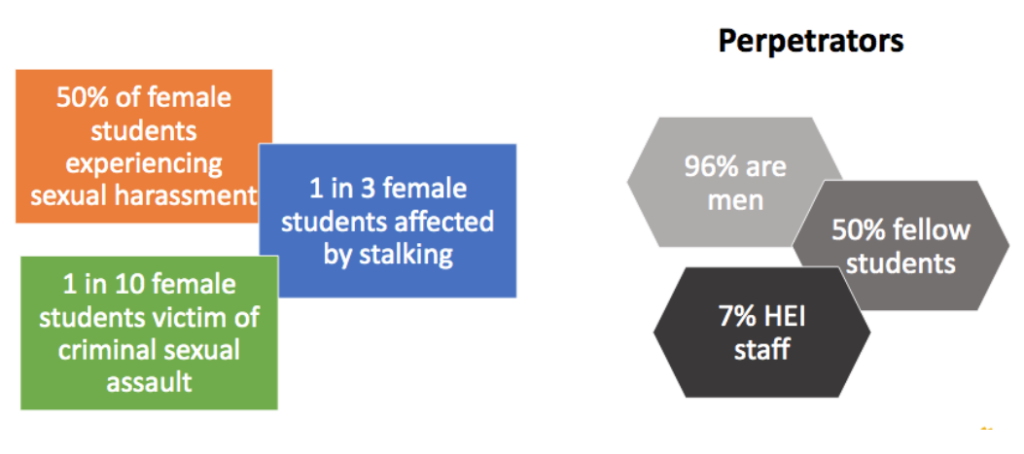

According to the study conducted in the frame of the project “Gender-based violence, stalking and fear of crime”, an European Union project (2012), which involved universities of Poland, Italy, Spain, Germany, UK, at least half of the female students surveyed had experienced sexual harassment at some point in their lives (51.1 %), more than a third had been affected by acts typical of stalking (36 %) and nearly one in ten students had been a victim of criminal sexual assault (8.7 %).

Moreover, 96% of the perpetrators were man, about half fellow students and 7% HEI staff.

The study revealed that results are very similar across the different involved countries.

GBV from University staff members against students

Even if GBV appears to be more widespread as a students to students phenomenon, it was also found how staff members at universities happen to be perpetrators against students.

In some countries such as in the UK, the issue has become a hot topic in public debate.

This was illustrated in a study by Lewis and Anitha (2019) were a series of events who caught the attention of a wide audience and a survey in particular are reported:

Sara Ahmed is a knowledgeable feminist scholar whose resignation from Goldsmith contributed to shed light on a phenomenon which tended to get poor visibility (https://feministkilljoys.com/2016/08/27/resignation-is-a-feminist-issue/).

A campaigning organisation in the UK, in collaboration with the National Students’ Union surveyed 1839 higher education students and involved 15 of them in focus group to find that the most of those who experience ‘sexual misconduct’ by a member of the staff, stated their complaints were not addressed by their Universities.

Source: Lewis, R. and S. Anitha Explorations on the Nature of Resistance: Challenging Gender-Based Violence in the Academy in G. Crimmins (ed.), Strategies for Resisting Sexism in the Academy, Palgrave Studies in Gender and Education, pp. 75-94.

GBV experienced by universities’ employees

In 2018 a study was commissioned in the US based on interviews with women employed at universities who had experienced at least one sexually harassing behavior in the last 5 years (Johnson, Widnall & Frazier, 2018).

Different forms of sexual harassment were reported, such as: sexual advances, lewd jokes or comments, disparaging or critical comments related to competency, unwanted sexual touching, stalking, and even sexual assault by a colleague.

Source: Johnson, P.A., Widnall, S.E. And F. Benya Frazier, Editors (2018). Sexual Harassment against women Climate, Culture, and Consequences in Academic Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. A consensus Study Report of the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering and Medicine. The National Academies Press, Washington DC.

Does it sounds weird? Not really, if we go back a few years ago to something which shocked the academic world……

In 2015, Tim Hunt, Nobel Laureate from the London University College, made a shocking public statement affirming that 3 things happen when women researchers are in a Lab with men.

In response, hundreds of researchers and scientists (men included) started the massive #distractinglysexy campaign on Twitter

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=OO7ome2Y7fU&feature=emb_logo

The one from Hunt was a stereotypical and biased belief that we can easily imagine can lead to a series of sexist jokes in the lab, jokes which were reversed by women in their campaign, with a very effective (and fun) rhetorical gimnick.

What can be done? Recommendations against GBV within institutional change for gender equality

Would having a GBV and sexual harassment aware and free University or Research Institution be a meaningful goal to achieve within an institutional change process? Our answer is definitely affirmative.

According to the project “It stops now. Ending Sexual Harassment and Violence in Third level education” (ESHTE) interventions at Universities should be based on 3 pillars that actually spotlight how and institutional change approach is crucial, and we add to this, related actions could be included in Gender Equality Plans:

An institution-wide approach:

- Take an institution-wide approach to developing policies and procedures for responding to incidents of gender-based violence against women students.

- Involve the students’ union in developing, maintaining and reviewing all elements of a cross-institution response.

- Assess interventions and policies regularly.

- Develop a sectoral representative body to develop guidance on how to handle disciplinary issues that may also constitute a criminal offence.

Prevention:

- Adopt an evidence-based programme seeking cultural change in the norms, beliefs and values that contribute to sexual violence.

- Develop partnership agreements between the student and university.

- Embed a zero-tolerance approach across all institutional activities including HR processes.

Intervention/response:

- Ensure a range of well-advertised supports are available on campus for victims/survivors.

- Develop a clear, accessible and representative disclosure response for incidents of sexual violence and rape; including a centralised reporting system.

- Conduct staff training.

- Develop and maintain partnerships with local specialist services.

- Establish and maintain strong links with the local police and health service.

Engaging men in ending violence against women

Men shall be actively involved across all areas of intervention when promoting institutional change, as highlighted and argued in the lesson by prof. Jeff Hearn. In this paragraph we are going to briefly sketch the main arguments to involve men in actions on GBV in particular: they can be used in advocacy, raising and training awareness work.

- Violence affects women and men. Just as with women, GBV directly affects men who have experienced GBV. But it also has indirect effects. In communities where GBV is present, women may develop fear or suspicion of all men due to the actions of a few. In addition, behaviour and attitudes that foster violence cankeep men from having close and meaningful relationships with each other. Furthermore, especially along class, race and ethnicity, sexual orientation and gender identity, disability and other discrimination axis, men can also be victims of GBV, as we have already explained above.

- Men have a responsibility to help prevent violence. GBV occurs because of the actions that some men (and some women) take. It is allowed to continue with impunity because non-violent men often do not get involved in changing the attitudes and beliefs that lead to violence.

- Men are in leadership positions. Men are the decision makers and main power holders in most communities and institutions. Gender norms and unequal power relationships, particularly those between men and women, underlie GBV.

We are also suggesting a series of roles that men could undertake, once engaged:

- Men as supporters participate in training and awareness raising activities on GBV, avoid language and jokes that condone or encourage GBV.

- Men as role models positively influence other men and boys. A role model sets an example showing that GBV is not acceptable and conveys this message to other men and boys.

- Men as agents of change. In this approach, men are proactively involved in trying to change norms that put women and girls, but also men and boys, at risk of GBV. They are engaged in challenging stereotypes and social norms that condone or encourage the perpetration of acts of GBV and try to influence policies and bring about organizational changes in their communities/institutions.

Targeting bystanders: from “bystanders” to “upstanders”. Interventions and campaigns

We have mentioned bystanders as one of the 3 key roles in GBV & sexual harassment. It is important that preventive interventions also target bystanders, and plenty of University interventions are actually focusing on this. Cambridge University for example chose to set up trainings and a support service targeting students to help them moving from a bystander to an ”upstander” position and urging to “breaking the silence”, as the title of the project itself said. Signalling that a certain behaviour is not socially approved, that you don’t like it, can be a powerful gesture that prevents situations from degenerating, state the organizers, and the only side effect ‘suffered’ by an upstander, might consist of experiencing some awkwardness and feeling uncomfortable in change, which can be overcome especially for such a good cause (watch the Breaking the Silence video here).

To conclude this lesson, we hope we have managed to show how complex the problem is, how relevant also for HEIs and Research Institutions, and to have provided you with arguments, tools and example to enable you to consider GBV when designing and implementing Gender Equality Plans and supporting institutional change processes. Feel free to comment and pose questions on this lesson in the forum section of the DOCC and undertake the assignment we have prepared for you!

References

UNCHR (2016), SGBV Prevention and response, training package

https://www.unhcr.org/sexual-and-gender-based-violence.html

European Commission(2016) Special Eurobarometer 449-Gender-based Violence

ESHTE project (2016), A review of data on the prevalence of Sexual Violence and Harassment of Women Students in Higher Education in the European Union

European Commission (2012), Gender-based Violence, Stalking and Fear of Crime-Project Report

https://eige.europa.eu/gender-based-violence/what-is-gender-based-violence

University of Exeter, The Intervention Initiative toolkit https://socialsciences.exeter.ac.uk/research/interventioninitiative/toolkit/

Lewis, R. and S. Anitha Explorations on the Nature of Resistance: Challenging Gender-Based Violence in the Academy in G. Crimmins (ed.), Strategies for Resisting Sexism in the Academy, Palgrave Studies in Gender and Education, pp. 75-94

Johnson, P.A., Widnall, S.E. And F. Benya Frazier, Editors (2018). Sexual Harassment against women Climate, Culture, and Consequences in Academic Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. A consensus Study Report of the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering and Medicine. The National Academies Press, Washington DC.